It’s been a couple of weeks since I returned from my latest adventure: a trip to eastern Indonesia. Specifically, it covered the islands of Sulawesi, Halmahera, New Guinea, and Waigeo.

What made me want to visit that area of the world in particular? The bird life is one of the big reasons, particularly the Birds of Paradise, which occur on Halmahera and the islands to the east. Eastern Indonesia is also home to a variety of spectacular parrots, a bird group I am particularly interested in.

Indonesia is also interesting from a biogeographical perspective because the animals found in eastern and western Indonesia are very different from each other. For instance, with regards to mammals, eastern Indonesia has marsupials, such as cuscuses, sugar gliders, and tree kangaroos. Western Indonesia is home to placental mammals, such as a variety of monkeys, apes, cats, and deer. In short, western Indonesia’s mammals are similar to those found on mainland Asia and eastern Indonesia’s are similar to those found on Australia.

The first European to write about this pattern was English explorer Alfred Russell Wallace, who traveled from Singapore to eastern New Guinea from 1854 to 1862. He wrote a book on his travels called the Malay Archipelago. – The Land of the Orang-utan, and the Birds of Paradise, A Narrative of Travel with Studies of Man and Nature. In the book, he describes the great diversity of plants and animals he found on the different islands he visited, as well as his interactions with the local people. He also describes the many trials he went through, which included numerous injuries, infections, boating mishaps, and bouts of malaria. It’s a fascinating book and was one of the things that inspired me to go on this trip. I’ll likely be quoting from this book frequently as I write up my Indonesia trip.

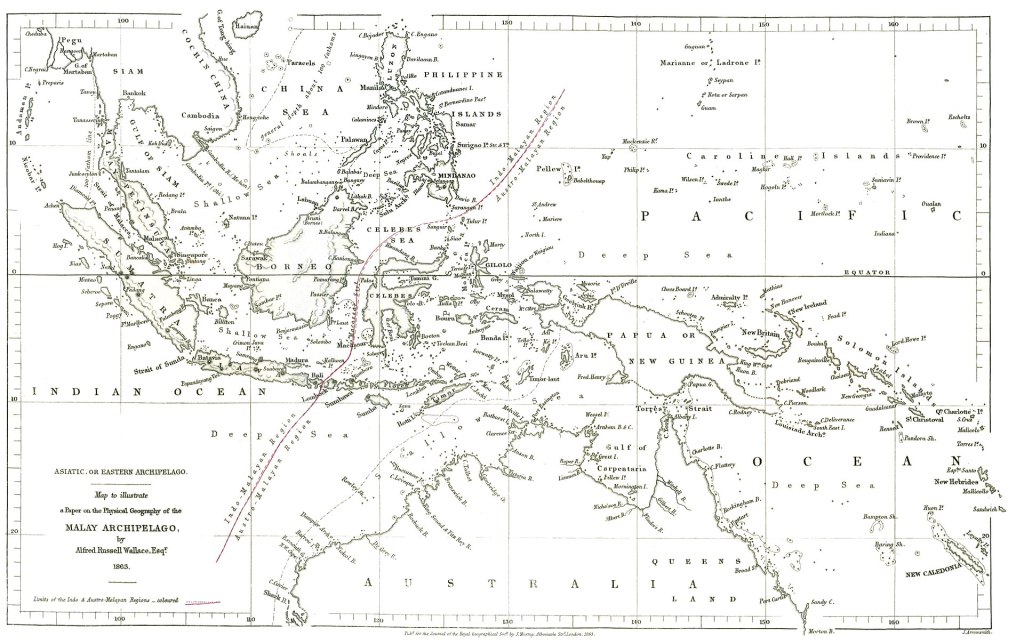

Wallace took copious notes on the plants and animals he saw on the different islands and he, along with a large crew of assistants, gathered thousands of specimens, most of which he sold to museums and other collectors. Wallace eventually wrote a paper on his observations of biogeography entitled On the Physical Geography of the Malay Archipelago. This paper included the below map, which shows a line dividing what he called the Indo-Malayan Region and the Austro-Malayan region.

Why is there such a difference in the fauna between the eastern and western Malay Archipelago? Wallace knew that the geological features of the Earth’s surface are not fixed, nor is the distribution of plants and animals. As he put it, “it is now generally admitted that the present distribution of living things on the surface of the Earth is mainly the result of the last series of changes that the surface has undergone.”

What kind of changes could lead to the interesting faunal distributions he found? Wallace obtained information on sea depths in and around the Malay Archipelago and took careful notice of where there were deep and shallow seas. Interestingly, there were deep seas right around where the break between the Indo-Malayan and Austro-Malayan faunal zones is located. So, he inferred that at one point, the islands west of Java and Borneo were once connected to mainland Asia. That allowed animals from mainland Asia to migrate to those islands. The islands to the west must have once been connected to Australia, which would explain why their fauna is similar to that of Australia.

We now know that, during the last major ice ages, much of the world’s water was tied up in ice sheets, which significantly lowered sea levels. During that time, Java, Sumatra, and Borneo were connected to mainland Asia, and New Guinea and some of the surrounding islands were connected to Australia. Mainland Asia and Australia, however, were never connected to each other due to the deep water that runs along the “Wallace Line.”

The tour I went on covered the region to the east of the Wallace Line, so much of the wildlife was related to that found in Australia. We started with the island of Sulawesi, which has a particularly interesting mix of birds and mammals due to its complex geological history. Different parts of the island have formerly been attached to either Asia or Australia, and other parts were formed by volcanic eruptions. Sulawesi therefore has animals that are related to those found on Asia (such as macaques and civets) and Australia (various species of cuscus).

The first place we visited on Sulawesi was Lore Lindu National Park. It is home to many endemic bird species (at least 77 of them) and an interesting mixture of mammals that includes a wild pig species (the babirusa), various marsupials, primates (including a macaque and a tarsier), and a small species of buffalo (the Anoa).

Getting to Lore Lindu from Palu was a bit of a wild ride. The road was paved and in decent shape but it was rather narrow. On most birding tours, everyone rides together in a van or minibus, but that would not work in this region because of the narrow, twisty roads. So, we had a convoy of four cars (there were seven people on the trip, plus the birding company guide, the Indonesian ground agent, and often other local guides).

People seem to drive super fast in Indonesia, and they use their horns constantly. There are also motorbikes zipping around everywhere and cars would often pass the motorbikes even on nearly blind curves. I’m quite glad I wasn’t the one driving – the speed and constant honking would just unnerve me. I would have also been scared of hitting someone.

I don’t think this area of Indonesia gets a lot of tourists. While we were birding on the roadside, a few young women on a motorcycle pulled up and asked if they could take selfies with us. They were quite chuffed when we allowed them to do so. That happened on Halmahera as well.

On the first day (which was kind of exhausting due to a 2 AM flight), we stopped to bird at a few places on the way to the lodging at a town called Wuasa. Some were stops on the side of the road where we found a variety of birds (including the below Collared Kingfisher). We also stopped at Lake Tambing, which I’ll write about later below because we ended up returning to it a few times.

This was a birding tour, but a lot of the invertebrates were hard not to notice. Large, colorful orb-weaver spiders were common and the big females were particularly conspicuous due to their bright yellow abdomens and elaborate webs. They also tend to sit right in the middle of their webs during the daytime. These spiders seem to have an eye for art, as they often add attractive zig-zag designs onto their already impressive webs. Some decorate their webs with other material as well.

We also went birding during the evening by a rice field near the town of Wuasa. Owls were the main target and we did get good views of two Australasian Grass Owls and a distant view of a Sulawesi Masked Owl. Several Great Eared Nightjars also showed up. Birds I managed to get okay to decent pictures of included the below Australasian Swamp Hen, Lesser Coucal, Yellow-billed Malkoha, and Pied Bushchat. Click the pictures to make them bigger. Alfred Wallace described the Yellow-billed Malkoha as being “one of the finest of the known cuckoos.” It is indeed a beautiful, eye-catching bird.

The next day, we started off very early to hike on the Anaso Track, which is the only long hiking trail in the park. We were the only hikers there, but we ran in to a few local people on motorbikes.

Lore Lindu is hilly and mountainous and is covered in very thick forest. The forest is beautiful but difficult to bird in, because a bird can be quite close by but still concealed by vegetation. Good, local guides are very helpful in such an environment. I wouldn’t have found much on my own.

Despite the challenge of birding in a thick forest, we did find a lot of interesting birds. The highlight for me was a pair of Diabolical Nightjars. This species was formerly called the Satanic Nightjar, and some people still call them that. I don’t know what they did to earn such a sinister-sounding name, though. These birds were very well camouflaged so I was quite impressed that the local guides had managed to find them.

The Purple-bearded Bee Eater was one of the target birds, as it is endemic to Sulawesi. We found a pair at the end of our time on the track. I did manage to get a picture of them, although it’s not great due to the poor lighting.

There was an overlook over a cliff (pictured below) that made a nice rest stop and birding area.

The birds were generally tricky to photograph which was due to the environment (thick vegetation and little light) and my amateur-level photography skills. However, the below Cerulean Cuckoshrike was very nice and posed for us in some decent lighting.

I found the plants along the Anaso track quite interesting. The track was very rich in tree ferns and Pandanus (screw pines), as well as lycopods. There was also one spot that had at least three different species of carnivorous pitcher plants. I’ve seen pitcher plants in North America as well, in California and northeastern Alberta. The “pitcher” leaf morphology has actually evolved multiple times in unrelated plant groups. The big advantage that the pitcher leaves provide the plant is a way of obtaining nitrogen other than through the roots. That way, pitcher plants can grow well in areas where the soil is low in nitrogen, or where there is no soil. Many Asian pitcher plants are actually epiphytes, which means that they grow off of other plants.

There were some rainbow eucalyptus trees in Lore Lindu as well. They are named for their multi-colored bark and are native to Indonesia, Papua New Guinea, and the Philippines. Because they are so attractive, they are grown as ornamental trees in many other countries with tropical or subtropical climates.

We headed to Lake Tambing after hiking the Anaso Track. The Lake Tambing area is well set up for visitors. There are trails, bathrooms (squat toilet only), water taps, places to sit, and a camping area. Someone who runs the area obviously enjoys plants because there are a lot of nice cultivated plants along some of the trails and an orchid house. There’s a little mosque on the grounds too, as Sulawesi is predominantly Muslim. However, there is a sizeable Christian minority and I also saw a nice Buddhist temple in Palu.

Lake Tambing was an enjoyable place to bird watch, although interestingly, there were no water birds around the lake. We saw a few Black-naped Orioles during our time there, which are very photogenic birds. They are not related to the orioles found in North America. North American orioles are in the blackbird family (Icteridae) and these ones are in the family Oriolidae.

One of the highlights of Lake Tambing was a Geomalia, a rare Sulawesi endemic from the thrush family. They can be quite shy but we saw one lurking around behind one of the buildings.

There were a lot of insects around Lake Tambing. People tend to view insects as pests, but many of the insects on Sulawesi were very striking, even beautiful. The butterflies and moths in particular often had brilliant coloration.

We also found the below Finch-billed Mynas (AKA Grosbeak Starlings) along the road in the Lore Lindu area the next day. They are communal nesters who dig out their nests in dead or dying trees.

Visitors to Lore Lindu who don’t want to camp at Lake Tambing can stay in nearby Wuasa. The itinerary warned that the lodging there was “basic,” so I was expecting something quite rustic but the place wasn’t so bad. It was clean and had electricity and running water. The only odd thing was that the bathroom had no shower. There were, however, two big rubber pails of water and a smaller wash bucket that could be used to shower with. The food they served was good.

After birding the Lore Lindu area, we headed to the Tangkoko Nature Reserve in northern Sulawesi, where we managed to see a few of Sulawesi’s unique mammal species and some gorgeous kingfishers and hornbills. That will be the topic of my next post.